The days and nights in Melbourne are icy cold, the wind like a slap to the cheek. What better excuse does one need to wrap up in a big old jacket and cosy on down to your local pub for some tunes and a glass of red. This Sunday I caught Woodward and Rough at The Lomond Hotel, performing to a small but grateful audience in their weekly 10pm time-slot. The beautiful lament of Coalmine Blues, the rhythmic drive of Streak O'lean, Streak O'fat, the dancing banjo of the Allen Brothers Rag -- and us in the audience, huddled at the tables between the chat and rumble of Sunday night drinkers and the rising swell of music from the stage.

I'll be posting a short interview with guitarist Warren Rough in the coming weeks. Woodward and Rough are playing at the Fox Hotel (Collingwood) this coming Sunday (5th July) 5-7pm. To purchase Woodward and Rough's Sweet Milk and Peaches and Hometown Blues please visit Accross the Borders.

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Saturday, June 26, 2010

Big Beat of the '50s -- June edition (117)

The June edition of Big Beat (official magazine of the Australian Rock 'n' Roll Appreciation Society) is now in print. Now up to it's 117th edition -- published quarterly -- the popular mag covers 50s rock 'n' roll news from around Australia including reviews, interviews, festival news, columns, feature articles and more. June's edition has an interesting article on music author and radio presenter Charlie Gillett who died in March of this year as well as an investigation into the origins of the term "rockabilly" and the style it became synonymous with. Local country/rockabilly band Gatorbait get a write-up on page 20-21 as does 'Melbourne Roots' which was a lovely surprise. (Thanks Big Beat) There is also a feature on the upcoming Victorian rock 'n' roll festival, Camperdown Cruise (22-24th October 2010). To buy an issue or become a subscriber please visit the Australian Rock 'n' Roll Appreciation Society website.

The June edition of Big Beat (official magazine of the Australian Rock 'n' Roll Appreciation Society) is now in print. Now up to it's 117th edition -- published quarterly -- the popular mag covers 50s rock 'n' roll news from around Australia including reviews, interviews, festival news, columns, feature articles and more. June's edition has an interesting article on music author and radio presenter Charlie Gillett who died in March of this year as well as an investigation into the origins of the term "rockabilly" and the style it became synonymous with. Local country/rockabilly band Gatorbait get a write-up on page 20-21 as does 'Melbourne Roots' which was a lovely surprise. (Thanks Big Beat) There is also a feature on the upcoming Victorian rock 'n' roll festival, Camperdown Cruise (22-24th October 2010). To buy an issue or become a subscriber please visit the Australian Rock 'n' Roll Appreciation Society website.Tuesday, June 22, 2010

The Crackajacks 'Long Blond Hair'

Below is a brilliant youtube clip of early 80s rockabilly band 'The Crackajacks' who had a cult-following with their song 'Long Blond Hair'. (See earlier post, under Crackajacks in the sidebar for more information on the band.)

Labels:

Melb Music History,

Rockabilly,

The Crackajacks,

Warren Rough

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

The Junes CD Launch - 12 Golden Greats Trades Hall, Carlton June 2010

Gleny Rae -- what a singer! Ramblin' Girl (video above) takes my breath away. Last Saturday (June 12th) I went with friends to glam/country band The Junes CD launch at Bella Union Bar (Trades Hall, Carlton) Great venue -- towering columns, sandpapered walls, grand ceilings, cold, wide staircases. It seemed to suit the winter mood. I wore a heavy, black woolen jacket and still stood shivering by the bar. The layered harmonies, cajun dance, and touch of Junes glamour soon warmed my cold journalists blood however and the suspended union/protest flags and red lamplight above me were stirring. The room had a fabulous sound.

The CD launched was The Junes: 12 Golden Greats (their first full length album, recorded with Craig Pilkington at Audrey Studios) and there are several heart-breakingly beautiful songs on this album. Slow dance, Blue Baby is a favourite, as is Hopeless and Ramblin' Girl (see video above) though I think this may be on their previous recording. The jumpier numbers like Stampede in the Begerkery (complete with chicken stomps, raised shins and sudden whoops) have a raucous hillbilly energy to them and are loads of fun. As per usual, there was a lot of innuendo and onstage banter to get the crowd laughing: Gleny Rae bemoaning the plight of chickens who are armless and without opposable thumbs; Sarah Carol teasing the all male rhythm section about their matching shirts and colourful on-stage bonding ;) etc. The fiddle and accordian solos by Glenny Rae were stunning, and Suzannah's singing was haunting and full of subdued passion. The rhytmm section (Dougie Bull and Chris Tabone) were very lively yet able to pull it back for the quieter numbers and let the beautiful, complex harmonies sing out.

As part of the evening's entertainment the 100+ or so crowd were treated to Cajun dance lessons (care of Emma Bee) and it was cute watching the, perhaps, dozen couples get up to left-foot, right-foot-it round the dance floor (and, yes, slightly dishearting to see that all the willing blokes were over sixty). My fellow lady friends and I stood slumped up against the wall slurping gin like lemonade as if we were abandoned prom nerds in a country barn. Once Andy Baylor's Cajun Combo started up however (see video below) we flung our boyfriend-needy inhibitions aside and toe-tapped our way onto the dance floor, swept up by the jaunty rhythms & melodies of the expert Cajun music. With such seasoned musicians as: Andy Baylor, Rick Dempster, Sam Lemann, Andy Scott, and Lenny Ramanauskas, what can I say? Brilliant. We danced the night away.

Needless to say it was a great gig. It all ended with a crammed ride in the cabin of a ute, gear stick vibrating madly at my calves, ashtray attached unwittingly to my bag stuffed under the dash, butts all over the floor -- cigarettes, that is ;) -- and several laughing heads growing out of my shoulders (or so it would have seemed to bemused pedestrians). This inane happiness I attribute to the fabulous Junes of course and the Cajun Combo -- not just the booze!

For more information on The Junes and to buy the CD visit their myspace page here. For Andy Baylor's Cajun Combo visit his website. H

Monday, June 14, 2010

Interview with Craig Woodward (Part Three of a three part series)

This is the third and final instalment of a three part interview with Craig Woodward. Please see earlier posts (filed under Craig Woodward/Interviews) for earlier instalments. Craig plays every Sunday from 10pm at the Lomond Hotel in Brunswick East as part of Woodward and Rough and also the first Friday of every month at Coburg's Post Office Hotel in the Flying Engine String Band. Go and see them! (Pictured: Aubrey Maher, Mick Cameron and Craig Woodward in the original line-up of the ACME String Band.)

This is the third and final instalment of a three part interview with Craig Woodward. Please see earlier posts (filed under Craig Woodward/Interviews) for earlier instalments. Craig plays every Sunday from 10pm at the Lomond Hotel in Brunswick East as part of Woodward and Rough and also the first Friday of every month at Coburg's Post Office Hotel in the Flying Engine String Band. Go and see them! (Pictured: Aubrey Maher, Mick Cameron and Craig Woodward in the original line-up of the ACME String Band.)HT: Now you travelled to America – twice I believe – once in 1998 and once just recently – a few years ago; how does the community and music here compare to over in the States? Did you get in touch with the communities over there that are playing old-time music?

CW: Yeah definitely. A way in for me was to go to a couple of festivals and conventions that they have over there and I was just lucky to meet the right people. People that I could spend time with who are kind of like the people I know here.

HT: So is it quite similar in some ways?

CW: Yeah, it’s very similar. I was lucky to camp next to the right crowd – for me, anyway. Because it’s funny …

HT: Is it bigger over there?

CW: Oh yeah – it’s huge. Actually the biggest festival, which is just string band/old-time music festival – it doesn’t include bluegrass – which is the Appalachian String Band Music Festival in West Virginia, Clifftop; they call it Clifftop. That’s gotten too big there and I think this year might be the last one because it’s just totally outgrown the site that it’s on and it’s just gotten so popular. I went there both times I went to the States and it was really huge; it was three years ago that I went and it’s sort over a weekend but people start showing up a weekend beforehand and I think on about the Thursday they just stop letting people in.

HT: Wow. So you’re talking attendances in the thousands? Tens of thousands perhaps?

CW: Maybe. (laughs)

HT: Too many people to count.

CW: Yeah. And it’s good but it’s a bit overwhelming; it’s a bit much you know.

HT: Did you play?

CW: Oh yeah, just jamming, you know. Which is mostly what goes on there. They have contests: fiddle contests, banjo contests; stuff like that. Which we don’t have here cause we’re the kind of people that get funny, I think, about the idea of contests … and it is funny.

HT: In Australia? (both laugh) Nobody wants to stand out?

CW: The Americans sort of grow up with a different sense of competition you know, they’re kind of into contests. But, you know, the good thing about the contests often is that if you play in a contest you get your entry money that you paid to get into the festival back. So it gets you in for free and it’s a way of getting musicians in and also having something on the stage that’s interesting for the locals to look at. You know, but everyone gets up; not just people that think they might have a chance at winning. (both laugh)

HT: Are there any old-fashioned pie-eating contests?

CW: I’d say so, I’d say so … Yeah, cherry pie; that’s popular in America.

HT: Is there a lot of dancing at those sort of festivals?

CW: Heaps of dancing. And that’s what we need here. They do a type of clogging – which is, they call it flat-foot dancing; although there might be a kind of difference between what people call clogging and what they call flat-foot, I’m not really sure. It’s kind of a cross between a few kinds of dancing, you know; it’s got a few influences but it’s very loose.

HT: It’s a high-stepping, rhythmic sort of dance, is that right?

CW: Yeah, yeah – though some of the really good flat-footing dancers do it really close to the ground; they hardly even lift they’re feet. So it’s not as exaggerated as some of those kinds of dancing.

HT: Does that come from Irish dance tradition?

CW: Yeah partly. Partly from that and, um, the African influence of course. Some of it’s similar – you’re probably thinking – to Irish step-dancing except much looser and not as exaggerated.

HT: Just getting back to the current music climate and what’s been happening in Melbourne and Victoria recently with the changes to liquor licensing legislation. Headbelly Buzzard – along with two other residency Railway gigs – lost their weekly spot late in 2009. Can you just talk a little bit about the impact the high-security measures had on you personally as well as a musician?

CW: Well … it’s definitely bad for those of us playing at the Railway. You know they keep going on about how Melbourne’s supposed to be Australia’s arts precinct and it’s not a very good way to go about keeping something that’s already an active culture going. And, you know, things might change; but they haven’t changed yet – for the Railway. And some places you’ve got security on but it really sets the wrong tone for a venue, having security on. It’s a bad look.

HT: In the fourteen years that Headbelly played at the Railway every Friday night, did you see any kind of violence or trouble?

CW: No.

HT: What sort of crowd did you get there?

CW: Well, it’s a pretty varied kind of crowd, pretty diverse. I mean pretty gentle generally; very gentle crowd. (laughs) Drinkers though! Lots of drinkers. Which was good ‘cause it kept us in a job as well. Unfortunately – well not unfortunately … the way we play old-time music, it makes it more enjoyable if you drink.

HT: So when the changes came in and you were informed that you lost your gig, how much notice were you given? Was it quite abrupt?

CW: No notice. We just … well, it was a funny night – the last night but I don’t want to talk too much about that but I went in and saw Peter [Negrelli – the publican] during that week and he said: it’s all over; we’re stopping all the bands. So we didn’t even get to do a last gig. Yeah, after fourteen or fifteen years. But we’ve waited around for long enough and I’m hoping that the Railway will get bands back on but it might take awhile. So, we’ll try it out at The Post Office Hotel (Coburg).

HT: Great; a new start for the latest incarnation of Headbelly Buzzard.

CW: With a wooden floor.

HT: Good dancing floor! Thanks very much Craig, for doing the interview. It was good talking to you.

CW: Good talking to you. Thanks.

HT: (laughing) Back to the whisky.

CW: Back to the whisky.

------------------------------

For more information on Headbelly Buzzard and Sandilands, please follow embedded links. Woodward and Rough, Headbelly Buzzard and Sandilands CDs are available from accrosstheborders.com.au

Thursday, June 10, 2010

Memory and Reflection: Live Music at the Railway Hotel

When I was in my late teens, back in the 1990s, my mother introduced me to the thriving roots-music community centered, in part, around North Fitzroy’s Railway Hotel. Headbelly Buzzard were just beginning their fourteen year Friday-night residency and were quickly establishing themselves as Melbourne’s most dynamic old-time string band. I remember seeing them there: Craig in his denim overalls and Irish flat cap, Nicola in a flowing skirt, fiddle poised on her arm, Mick like some spunky, subterranean Neanderthal with a low-hung guitar and twinkle in his eye. The music was fiery, rhythmic. The crowd loved them. As the years passed Mum invited me to these Railway gigs to see all-female country band GIT, the rootsy, fiddle playing Buzzards, the electrifying Brunswick Blues Shooters. I quickly fell in love. I came back, again and again. Years later I met my future partner at The Railway; he was a tall, quiet young guy with sculpted cheek-bones, a mop of curly brown hair, sensual lips, and cool blue eyes. I would sometimes feel him watching me from the shadows of the blue-lit pub as I danced to the Blues Shooters in tight jeans and jangly earrings. When we got together, it was to play music; we sang ‘Georgia on My Mind’ at the old piano at the Lomond Hotel. We fell in love.

Jess and I went to The Railway most Thursday nights before our child was born to drink wine and dance and he would sit in with The Blues Shooters to play guitar or I would sing an old jazz tune to the familiar faces in the crowd. We were the next generation of musos – always offered opportunities to get up and perform. I remember (yes, fondly) the faux-marble floor, awful fluorescent lights, wood veneer tables and footy memorabilia on the walls. I remember the grapevines growing on trellises in the courtyard out back; the rich smells of the home-style pub food cooked by the publican’s wife, Miriam, in the kitchen; the faces at the bar, young and old, who would greet each other with a pot of beer and plenty of talk; Peter’s resigned, slightly grumpy, nod in greeting. But most of all I remember the bands. The live music community at The Railway was a given, like the air we breathed; it was our heritage.

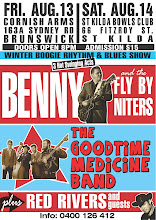

It was such a shock then, when late in 2009 the Italian publican, Peter Negrelli, informed the bands that due to changes in liquor licensing legislation (stating the pub required video surveillance and two licensed security guards when providing entertainment) the pub could no longer afford to put on gigs. As a result, both Headbelly Buzzard and The Brunswick Blues Shooters (who had played every Thursday night for four years) were instantly out of work. This was a blow to the whole community. My partner’s band ‘The Goodtime Medicine Band’, who had held the Saturday night spot at The Railway Hotel for a year and a half, also lost their gig. I don’t need to tell you the implications of this for us personally or for the broader music community; the bare bones are frightening enough: several generations of Melbourne roots musicians were culled by poorly conceived legislation that labeled live music – a culturally diverse and celebratory practice, known for encouraging strong community – a cause of alcohol-fuelled violence.

Ever since the debate has been raging: on the streets, in parliament and in the pubs where our strong music communities, of all genres, have been vocal about their anger at the linking of live music to alcohol-fuelled violence. It was at The Railway, in fact, that civil rights lawyer Anne O’Rourke began campaigning with fellow live music supporters Quincy McLean and Helen Marcou of Save Live Australian Music (SLAM) to fight for the link between ‘high risk’ conditions and live music to be overturned. This work, along with the support of other members of the industry led to the hugely successful SLAM rally that drew over 10,000 supporters into the city to protest against the reformed liquor licensing laws. At the time of the rally, in a spirit of goodwill, an accord was signed by the Brumby Government stating their intention to review the impact of the laws on small venues. The onus was still on the venues however and the review process complicated. It wasn’t until April’s petition delivery to Parliament (presented by nine well-known Victorian musicians) and a lot of bad press, that a couple of venues who had applied for the roll-back were finally approved. In the meantime gigs were being dropped all over the state. To date, only a small handful of venues have been successful. A new Director of Liquor Licensing has been appointed to replace the controversial Sue MacLellan and we are yet to see how or if this will change things for live music.

If you walked into The Railway Hotel today you’d find the food is still great, the fish-tank bubbling, the grapes still growing out back, but the music has largely disappeared and half the community with it. Headbelly Buzzard disbanded (they have recently reformed in a new line-up as ‘The Flying Engine String Band’ – see sidebar for details), The Brunswick Blues Shooters are still looking for a new residency, and The Goodtime Medicine Band are down from two gigs per week, to one (Lomond Hotel, Sundays 9pm). And what of the new bands that may have come through? So much lost opportunity. All of a sudden my mother’s words take on new meaning: “Headbelly Buzzard are a Melbourne Institution”, she’d said. It is devastating that the Government has been able to change the course of Melbourne’s music history so suddenly, in such an arbitrary way. It is inexcusable that this can happen whilst The Railway Hotel remains advertised on the State governed Tourism Victoria’s website as a pub popular for hosting live acoustic music. The hypocrisy is laughable. Is this all our culture means to Government – a sales pitch?

History is personal. If you close your eyes for a moment too long our heritage is gone; the place has been culled, renovated, replaced with high-rise apartments or hotels (as in the old city square) and, unforgivably, casinos. Then the culture dies, and our memories with it. Who are we then – when all we have left to remind us of our identity are faceless corporations, nightclubs and gaming joints? Who do we become? Voiceless? Disenchanted? Violent perhaps? I’ve been reading a novel lately: ‘Conditions of Faith’ by Melbourne-based author Alex Miller. In it his character ‘Antoine’ says: “The only history that satisfies our sense of justice is the history we write ourselves”. Yes. We won’t let our music history be overwritten. Music is voice, a powerful one; a voice that speaks from our most basic human need for culture and belonging. The Government has a big responsibility to the people who make up our cultural heritage in Victoria. And we have a big responsibility to fight for it, to protect it. We have a responsibility to remember.

Below is a youtube clip I found of Headbelly playing at the Railway in 2007 at Mick Cameron’s 50th. Though the footage is quite dark it is well worth persisting (it gets a bit easier to see when the b’day cake comes out) – the music is incredible and the energy and community captured on film is stunning. It is a poignant reminder of what we have lost and what we are still fighting for. H

Jess and I went to The Railway most Thursday nights before our child was born to drink wine and dance and he would sit in with The Blues Shooters to play guitar or I would sing an old jazz tune to the familiar faces in the crowd. We were the next generation of musos – always offered opportunities to get up and perform. I remember (yes, fondly) the faux-marble floor, awful fluorescent lights, wood veneer tables and footy memorabilia on the walls. I remember the grapevines growing on trellises in the courtyard out back; the rich smells of the home-style pub food cooked by the publican’s wife, Miriam, in the kitchen; the faces at the bar, young and old, who would greet each other with a pot of beer and plenty of talk; Peter’s resigned, slightly grumpy, nod in greeting. But most of all I remember the bands. The live music community at The Railway was a given, like the air we breathed; it was our heritage.

It was such a shock then, when late in 2009 the Italian publican, Peter Negrelli, informed the bands that due to changes in liquor licensing legislation (stating the pub required video surveillance and two licensed security guards when providing entertainment) the pub could no longer afford to put on gigs. As a result, both Headbelly Buzzard and The Brunswick Blues Shooters (who had played every Thursday night for four years) were instantly out of work. This was a blow to the whole community. My partner’s band ‘The Goodtime Medicine Band’, who had held the Saturday night spot at The Railway Hotel for a year and a half, also lost their gig. I don’t need to tell you the implications of this for us personally or for the broader music community; the bare bones are frightening enough: several generations of Melbourne roots musicians were culled by poorly conceived legislation that labeled live music – a culturally diverse and celebratory practice, known for encouraging strong community – a cause of alcohol-fuelled violence.

Ever since the debate has been raging: on the streets, in parliament and in the pubs where our strong music communities, of all genres, have been vocal about their anger at the linking of live music to alcohol-fuelled violence. It was at The Railway, in fact, that civil rights lawyer Anne O’Rourke began campaigning with fellow live music supporters Quincy McLean and Helen Marcou of Save Live Australian Music (SLAM) to fight for the link between ‘high risk’ conditions and live music to be overturned. This work, along with the support of other members of the industry led to the hugely successful SLAM rally that drew over 10,000 supporters into the city to protest against the reformed liquor licensing laws. At the time of the rally, in a spirit of goodwill, an accord was signed by the Brumby Government stating their intention to review the impact of the laws on small venues. The onus was still on the venues however and the review process complicated. It wasn’t until April’s petition delivery to Parliament (presented by nine well-known Victorian musicians) and a lot of bad press, that a couple of venues who had applied for the roll-back were finally approved. In the meantime gigs were being dropped all over the state. To date, only a small handful of venues have been successful. A new Director of Liquor Licensing has been appointed to replace the controversial Sue MacLellan and we are yet to see how or if this will change things for live music.

If you walked into The Railway Hotel today you’d find the food is still great, the fish-tank bubbling, the grapes still growing out back, but the music has largely disappeared and half the community with it. Headbelly Buzzard disbanded (they have recently reformed in a new line-up as ‘The Flying Engine String Band’ – see sidebar for details), The Brunswick Blues Shooters are still looking for a new residency, and The Goodtime Medicine Band are down from two gigs per week, to one (Lomond Hotel, Sundays 9pm). And what of the new bands that may have come through? So much lost opportunity. All of a sudden my mother’s words take on new meaning: “Headbelly Buzzard are a Melbourne Institution”, she’d said. It is devastating that the Government has been able to change the course of Melbourne’s music history so suddenly, in such an arbitrary way. It is inexcusable that this can happen whilst The Railway Hotel remains advertised on the State governed Tourism Victoria’s website as a pub popular for hosting live acoustic music. The hypocrisy is laughable. Is this all our culture means to Government – a sales pitch?

History is personal. If you close your eyes for a moment too long our heritage is gone; the place has been culled, renovated, replaced with high-rise apartments or hotels (as in the old city square) and, unforgivably, casinos. Then the culture dies, and our memories with it. Who are we then – when all we have left to remind us of our identity are faceless corporations, nightclubs and gaming joints? Who do we become? Voiceless? Disenchanted? Violent perhaps? I’ve been reading a novel lately: ‘Conditions of Faith’ by Melbourne-based author Alex Miller. In it his character ‘Antoine’ says: “The only history that satisfies our sense of justice is the history we write ourselves”. Yes. We won’t let our music history be overwritten. Music is voice, a powerful one; a voice that speaks from our most basic human need for culture and belonging. The Government has a big responsibility to the people who make up our cultural heritage in Victoria. And we have a big responsibility to fight for it, to protect it. We have a responsibility to remember.

Below is a youtube clip I found of Headbelly playing at the Railway in 2007 at Mick Cameron’s 50th. Though the footage is quite dark it is well worth persisting (it gets a bit easier to see when the b’day cake comes out) – the music is incredible and the energy and community captured on film is stunning. It is a poignant reminder of what we have lost and what we are still fighting for. H

Friday, June 4, 2010

Interview with Craig Woodward (Part Two of a three part series)

This is part two of a three part interview from Sat 15th May, 2010. For the complete introduction and first instalment please view the earlier post: Interview with Craig Woodward (Part One of a three part series)

This is part two of a three part interview from Sat 15th May, 2010. For the complete introduction and first instalment please view the earlier post: Interview with Craig Woodward (Part One of a three part series)HT: Your former band, Headbelly Buzzard (pictured), have long been referred to as a ‘Melbourne Institution’. What was it about Headbelly, do you think, that generated such strong interest and respect from the music-going community?

CW: Can you say that last bit again? (laughs)

HT: (laughs) this is one of my longer questions! What was it about Headbelly, do you think, that generated such strong interest and respect from the music-going community? I mean, you guys had a pretty devoted audience at your Friday night gig at the Railway Hotel; there was a real buzz around it.

CW: I think that goes back to the trance thing; it can generate a good mood in a room, that trance style of simple tunes – it’s just a repetitive thing, played over and over again, you know. It was very much a groove based band. I mean we had some interesting tunes as well but I think it’s the rhythm that kind of made it work in a hotel [pub], not too loud also but it’s got a bit of drive to it as well without being too aggressive.

HT: Did you get a lot of dancers?

CW: Not as many as we would like. People in Melbourne are often a bit shy of dancing; but we’re working on it.

HT: We’re very good at wearing black though.

CW: (chuckles) Yeah. Makes it hard to see ya. Um, we have got some dancers and we’re hoping for more. The Flying Engine String Band is kind of the same band with different people in it – we’re playing a lot of the same repertoire but it sounds different ‘cause there’s different players and having the knee-injection of Johnny on the guitar provides a lot of drive – it’s maybe a little peppier than the old band. Which is exciting for the dancers.

HT: Also Johnny’s a different generation to you guys as well so there’s a whole new potential appeal there. He’s of my generation; ‘Gen. Y’ they call us.

CW: Yeah, that’s right.

HT: And there’s a lot of people my age who are becoming interested in this sort of stuff.

CW: That’s great. Finally! There wasn’t when I was your age – when I was interested in this kind of stuff. (laughs) But I’m glad their finally is – that’s great. I guess more obscure music styles are pretty accessible these days and if you are interested in old-timey music and you’re lucky enough to live in Melbourne – particularly around the inner north – there’s a very healthy scene of people playing this old-time string band music.

HT: How would you describe the community around the old-timey scene? I know you go to fiddlers conventions, festivals etc. Can you talk a bit about what sort of avenues there are out there for people who play – or are interested in – this sort of music?

CW: I think the thing that’s really keeping it healthy is the regular jam session at the Lomond Hotel. Often you get to learn a new style of music or whatever but you kind of get a circle of friends with it as well. (laughs) You end up spending time with these people because they’ve heard about the jam session and started coming along.

HT: Where do people come from? Are they locally based?

CW: All over. Some people come from out of town but, yeah, there’s quite a few people who live around here that come – but there are a few people that travel a bit.

HT: And what about the fiddlers conventions that you go to? Who organizes them? You mentioned Ken McMaster …

CW: Yeah, he organizes the Yarra Junction Fiddlers Convention. It’s kind of – it’s actually become two different conventions, so I’m not sure what’s going to happen but this year there was two: one at Blackwood in February and there’s one just gone a couple of weeks ago at Camp Eureka (Yarra Junction). There’s also – there’s actually three or four of those type of festivals a year now. There’s the Harrietville Bluegrass festival near Bright which is run by the Dear family, who also run the Piggery. It’s kind of a bluegrass and old-time convention. Nick Dear is a well-known Australian bluegrass, old-time and Cajun musician. He helped steer me in the right direction when I first started getting interested in string-band music.

HT: How many people attend those festivals do you think?

CW: Oh, I’m terrible at estimating. Between two and a few hundred maybe? You never see everyone at once so I don’t know (laughs). Especially now; it takes over the whole town – it’s a tiny town but there’s quite a few people and the difference I suppose between a – why it’s a convention is that it’s kind of a pickers festival like there’s concerts and stuff like that so you can go and listen to heaps of music. There’s a lot of jamming and there’s maybe a few workshops for people that want to come and learn some technique. So I guess that’s why it’s a convention. It’s mostly people that play who go rather than just people that are going out to see music.

HT: So there’s probably three or four festivals like that a year in Victoria, is that right?

CW: Well there’s one in Beechworth that’s been going for awhile. We went for the first time last year and that was really good. So we’re going back again this year.

HT: Do you camp out there? It’s over a couple of days, isn’t it?

CW: Yeah. It’s really cold. It’s on in August or something. We all stay in this big old priory. It’s like a nun house. (laughs)

HT: A nunnery? (laughs) Okay. Do you wear habits?

CW: No. Oh yeah I’m wearing a few habits but … (both laugh)

HT: We’re all wearing a few habits, I think. Um, so that’s in Beechworth – what is it, a big old house?

CW: Yeah it’s huge and it’s a bit like a maze. If people find their way around this year – it’s a really crazy layout.

HT: Is it open to anybody who goes along to the festival? How do you get invited?

CW: Yeah, yeah. There’ll be a website I suppose. That’s probably a good place to stay ‘cause that’s where the majority of the jam sessions happen. There’s all these different rooms and there’s just a big garden. So it was good, you know; it’s been going for awhile but I hadn’t actually made it there ‘till last year and I’m looking forward to going back. There’s a banjo jamboree in Guildford which sort of includes that kind of music: string band and bluegrass music but it’s not as specific as – cause, you know, Beechworth and Harrietfield the focus is kind of bluegrass and old-timey string band music, Cajun music – just sort of American (mostly southern) traditional music styles.

HT: Are you surprised that – considering there’s such a strong community of people that like this sort of music and play and attend these festivals – that there isn’t anything written about it in Melbourne?

CW: Yeah, in a way. In another way we don’t want everyone to find out because then we’d have to share it with too many people and things get ruined that way. (laughs) But I do think it’s well worth documenting because Melbourne’s got a thriving roots scene and it’s unique from what I’ve witnessed and heard from travelers who’ve come here. It’d be hard to find a roots scene like Melbourne’s in the U.S. – particularly in the South. People in the South are into NASCAR racing and bad country music.

HT: (laughing) Great. This sort of leads us into the next question, which is around the idea of traditional music and the reinterpretation of American music – particularly in Australian culture. What are your views on it? Is there room for bands to open it up to new genres or new styles of playing?

CW: There seems to be. There’s a lot of … interest at the minute – there’s a lot of interest in things like – or more interest in stuff that’s: like that but isn’t that, you know? So … there’s plenty of room [for reinterpretation] and that’s okay. Because people who are interested in stuff that’s like something [traditional] might follow it up a little and be interested enough to hear the original stuff. I just mean stylistically; I think it’s necessary to keep the tradition going and evolving rather than just playing something as a museum piece. I think reinterpretation can be good but most of it isn’t so I don’t know if it’s necessarily reinterpretation because I think to change something, you maybe should learn to do it first, before you change it.

HT: What about the song content or the lyric aspect of it – interpreting it for an Australian audience?

CW: Well it’s mostly instrumental the stuff that I usually play and there are lyrics in some of it but a lot of it’s nonsense lyrics and just gives the tune a little extra shift here and there to put a verse in. There are some songs that maybe come a bit more from the ballad form – the English kind of ballad form – but mostly we play more hypnotic kind of instrumental music, some of which has lyrics. So I’ll leave that up to someone else to work with the lyrics to make it a bit more Australian.

HT: Well Mick Cameron was very good at that.

CW: Yeah, that’s right. I used to leave it up to Mick but now, I don’t know; I’ve been playing some stuff with Alan Wright who used to do some of his songs that he’s written with Tony Hargreaves um maybe to make a recording or something – I’m not sure. But that’s kind of interesting to do something different. It’s kind of a bit challenging; it’s not as simple as the music I’m used to playing but some of it sounds pretty good.

HT: How is it different?

CW: There’s many more chords. It’s not that usual. You know we play stuff with one or two chords (laughs). I’m more into, um, thinking about the rhythms and phrasing rather than – I mean sitting, trying to play stuff off charts and I don’t even really know what those chords are. I’m playing mandolin and once I hear it enough I can sort of play something; we’re trying to follow the chords – it’s the way he wrote the song: a lot of chord substitution like what they use in jazz and stuff; it’s not jazz music but it’s not what I’m used to doing so that’s one of the reasons I thought it might be good to do, to improve my music knowledge a little bit.

HT: Yep. Extending a bit further. And just going back to Mick [Cameron] again, you used to play with him in Headbelly Buzzard and also in Sandilands and the Cajun Aces. Can you talk a little bit about Mick’s songwriting and playing style? He was very well respected in the Melbourne scene wasn’t he?

CW: Yeah, he sure was. We were playing in three bands together when he died [March 2008]. I don’t think anyone can play as simply; I really respected his simplicity, his playing, his songwriting, and tune writing.

HT: What are some of your favourite songs of Mick’s?

CW: Well I kind of like the songs on the first Sandilands CD we did [Waterhole]; some of which we just sort of stopped doing after awhile. Very kind of country-blues style rhythms. [pause] I have trouble remembering titles; I know the tunes.

HT: That’s okay. Waterhole is still available from accrosstheborders.com.au. How did playing with Mick differ going from Headbelly to Sandilands do you think? In terms of the style and the experience.

CW: Yeah, it was completely different. It was kind of fun because I kind of got Mick interested in old-time string band music, so I guess he was doing my thing with me and Sandilands was very much his interest in his song-writing and approaching it in a particular way so it was kind of like me doing his thing with him. And aside from that we used to be able to play the slowest; we used to be the slowest playing band in town on some of Mick’s stuff. (laughs) And it’s just sort of the other end of what we were doing in Headbelly Buzzard; Mick would be working in the engine room pounding out rhythm whereas in Sandilands he was kind of leading the tunes and I was trying to tinkle away on the banjo-mandolin in between it and, you know, kind of fill it out a bit and give it some extra dynamics.

HT: What about the old Headbelly Buzzard gigs; how many did you used to get in attendance?

CW: Well it was up and down I suppose; we were there for so long. There was always a fair few people there and if people wanted to see the band they knew where and when to see us so … I like doing residencies, I think playing locally people know where you are and you get to – you don’t always know everyone that’s there but often you know most of the crowd. On the big nights you get to meet new people as well.

HT: Do you think it was the authentic sound of Headbelly that attracted so many followers?

CW: I guess. But a lot of people didn’t know what it was – so I don’t know how authentic it was to them. But I guess it’s authentic in that we don’t intentionally try and change things much – the tunes I mean – from how we heard them. It’s kind of traditional in that way. But we still had kind of a unique sound, you know. I guess that’s what happens with this style of music when everyone’s playing the same tunes but you’re gonna play it the way you play it so you do tend to sound a bit different from each other. And plus coming from here (Australia) and not really having that many people to learn from – when we started, there wasn’t as big a community of people playing old-time music as there is now …

HT: Do you think perhaps you’ve been an influence in that regard – to the local scene?

CW: Yeah, I think so. A lot of the people that play now come down to the jam session and also have their own string bands and stuff. They first heard old-timey music at the Railway listening to Headbelly Buzzard then started learning banjo and fiddle and stuff like that. I also teach a lot of fiddle, banjo and mandolin as well.

HT: So you’ve inspired people to pick up their instruments and join in; that’s great. People bring their kids down to the Lomond sessions too don’t they? And some of the kids are playing along – helped out by the adult players?

CW: Yeah, that’s right. I think, around here, it’s a good time to be playing it because there are so many people coming along and festivals and sessions and jam parties; so there’s an easy way in.

-------------------------------------------

For more information on Headbelly Buzzard and Sandilands, please follow embedded links. Woodward and Rough, Headbelly Buzzard and Sandilands CDs are available from accrosstheborders.com.au

This is part two of a three part series which will be published in weekly instalments. Melbourne Roots would like to thank Craig for his thought provoking and generous responses. Stay tuned for the next instalment!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)